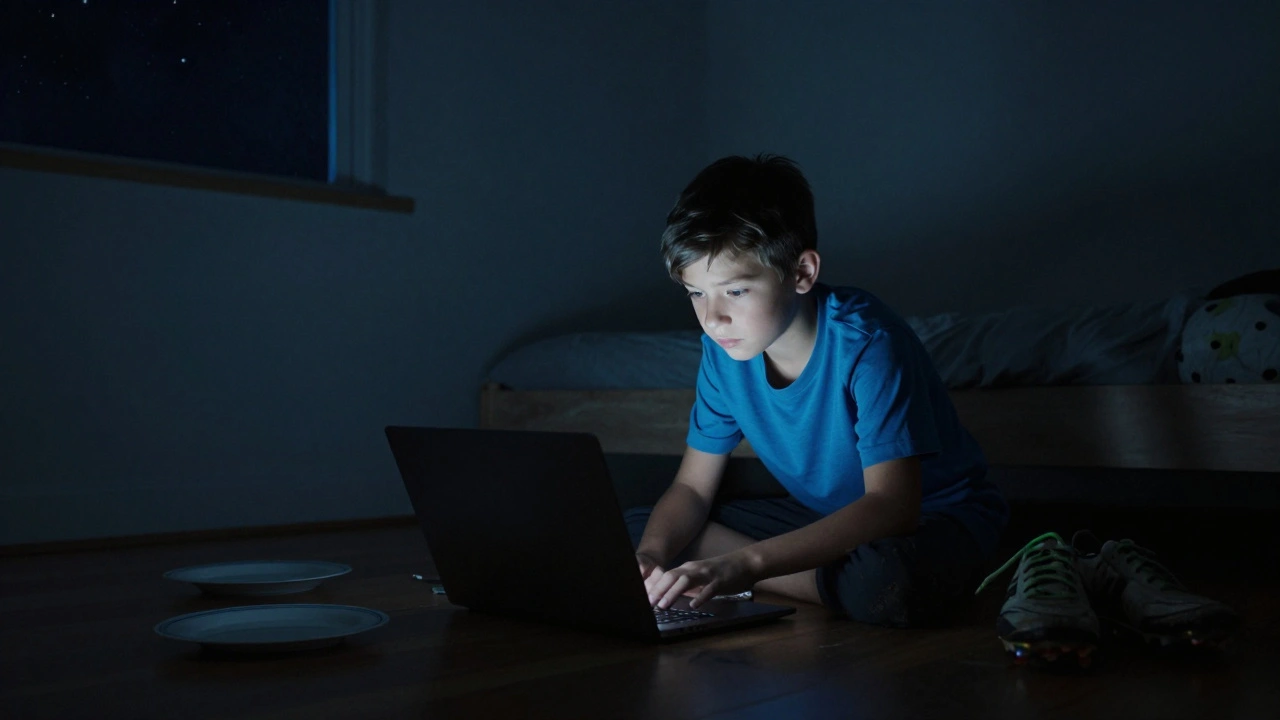

More kids are spending hours in front of screens than ever before. By age 12, the average child in the U.S. has played over 2,000 hours of video games. That’s more time than most spend in a full school year. But what happens when playing turns into a compulsion? When games become the only thing that makes a child feel in control? That’s when childhood gaming addiction starts - and it’s not just about playing too much. It’s about what’s missing in their real life.

What Is Childhood Gaming Addiction?

Gaming disorder isn’t just a buzzword. The World Health Organization officially recognized it in 2018 as a mental health condition. To qualify, a child must show clear signs for at least 12 months: losing control over gaming, prioritizing it over everything else, and continuing despite negative consequences. It’s not about how many hours they play - it’s about what they give up to play.

Some kids play 10 hours a day. Others play just three, but still skip meals, miss school, or shut out friends. One 10-year-old in Portland stopped talking to his parents after school. He’d lock himself in his room, come out only to eat, and go right back in. His grades dropped. His soccer team cut him. He didn’t cry. He just kept playing.

Why Kids Get Hooked So Fast

Games aren’t designed to be harmless. They’re built using psychology tricks that target developing brains. Dopamine spikes every time a player levels up, wins a match, or unlocks a rare item. For kids with low self-esteem, social anxiety, or unstable home lives, these digital rewards feel safer than real-world ones. A child who gets bullied at school can become a hero in a game. A kid who feels ignored at home can lead a team of 50 online players.

Studies from the University of Oregon in 2024 found that children who experienced emotional neglect were 3.2 times more likely to develop gaming addiction by age 11. The game wasn’t the problem - the loneliness was.

Early Signs You Can’t Ignore

It’s easy to brush off heavy gaming as a phase. But there are clear red flags:

- Refusing to stop playing, even when asked - and reacting with rage, tears, or silence

- Declining school performance, missing homework, or skipping class

- Loss of interest in hobbies, sports, or friends they used to love

- Sleeping less than 6 hours a night because they’re gaming late

- Lying about how long they’ve played or hiding devices

One mother noticed her 8-year-old daughter would whisper to her phone at night. She thought it was a friend. It turned out the girl was talking to strangers in a multiplayer game, convinced they were her only real friends. That’s not normal. That’s a cry for help.

How the Brain Changes

The prefrontal cortex - the part of the brain that handles impulse control, planning, and emotional regulation - doesn’t fully develop until around age 25. Kids are naturally more impulsive. Gaming addiction worsens this. Constant reward cycles weaken their ability to delay gratification. They start needing bigger, faster highs just to feel okay.

Brain scans from Stanford’s Child Development Lab in 2025 showed that children with gaming addiction had lower activity in areas linked to decision-making and empathy. Their brains were rewiring themselves to treat gaming like a survival need - not a pastime.

What’s Really Missing?

Most kids don’t get addicted to games. They get addicted to what games give them: control, belonging, purpose. If a child feels powerless at home or school, they’ll find power in a game. If they’re lonely, they’ll find connection in a guild. If they’re bored, they’ll find excitement in a battle royale.

The real issue isn’t the screen. It’s the silence behind it. Kids who are gaming excessively often have unmet emotional needs. They’re not lazy. They’re not spoiled. They’re trying to fill a hole no one noticed.

What Works - And What Doesn’t

Many parents try to ban games. That usually backfires. It creates power struggles, secrecy, and resentment. Other parents just give in, thinking it’s harmless. That doesn’t work either.

What does work? Structure with empathy.

- Set consistent limits - not as punishment, but as part of a daily routine. Example: 60 minutes after homework and chores.

- Play with them sometimes. Not to monitor, but to connect. Ask what they like about the game. Listen without judging.

- Replace gaming time with real-world rewards. A hike. A board game night. A cooking project. Something that gives them the same sense of achievement.

- Get them involved in teams - sports, music, volunteering. Real relationships rebuild what games stole.

One family in Eugene, Oregon, started a weekly "No Screens" Friday. They cooked together, walked the river trail, and played cards. At first, the 11-year-old screamed. After three weeks, he started asking to plan the next Friday. He didn’t quit gaming. But he started living again.

When to Seek Help

If a child has been gaming for over a year and shows three or more of the warning signs, it’s time to talk to a professional. A child psychologist trained in behavioral addiction can help. Therapy often focuses on building emotional skills, not just cutting screen time.

There are no quick fixes. Recovery takes months. But early intervention works. Kids under 12 who get support have an 80% success rate in regaining balance - if their parents stay involved.

What Parents Need to Know

You didn’t cause this. You’re not failing. But you’re the most important part of the solution. Your presence, patience, and willingness to understand matter more than any app blocker or time limit.

Games aren’t evil. But they’re powerful. And for a child still learning how to feel, they can become a prison - unless someone helps them find the door.