When a city or state changes its public health policy, the effects don’t show up in reports right away. But if you look closely at the data before and after the change, patterns emerge that can’t be ignored. Take smoking rates in Oregon after the 2023 statewide ban on flavored tobacco products. Within 18 months, youth smoking dropped by 22%. That’s not a guess. It’s pulled from state health surveys tracking over 15,000 teens annually. This isn’t an isolated case. Similar shifts have been documented across the U.S. and Europe when policies on air quality, sugar taxes, or needle exchange programs were implemented.

What Does "Prevalence" Actually Mean in Public Health?

Prevalence isn’t just a fancy word for "how common." It’s the total number of people living with a condition at a specific time, divided by the total population. For example, if 4,500 people out of 100,000 in a county have type 2 diabetes in 2024, the prevalence is 4.5%. This number changes over time - and policy can move the needle.

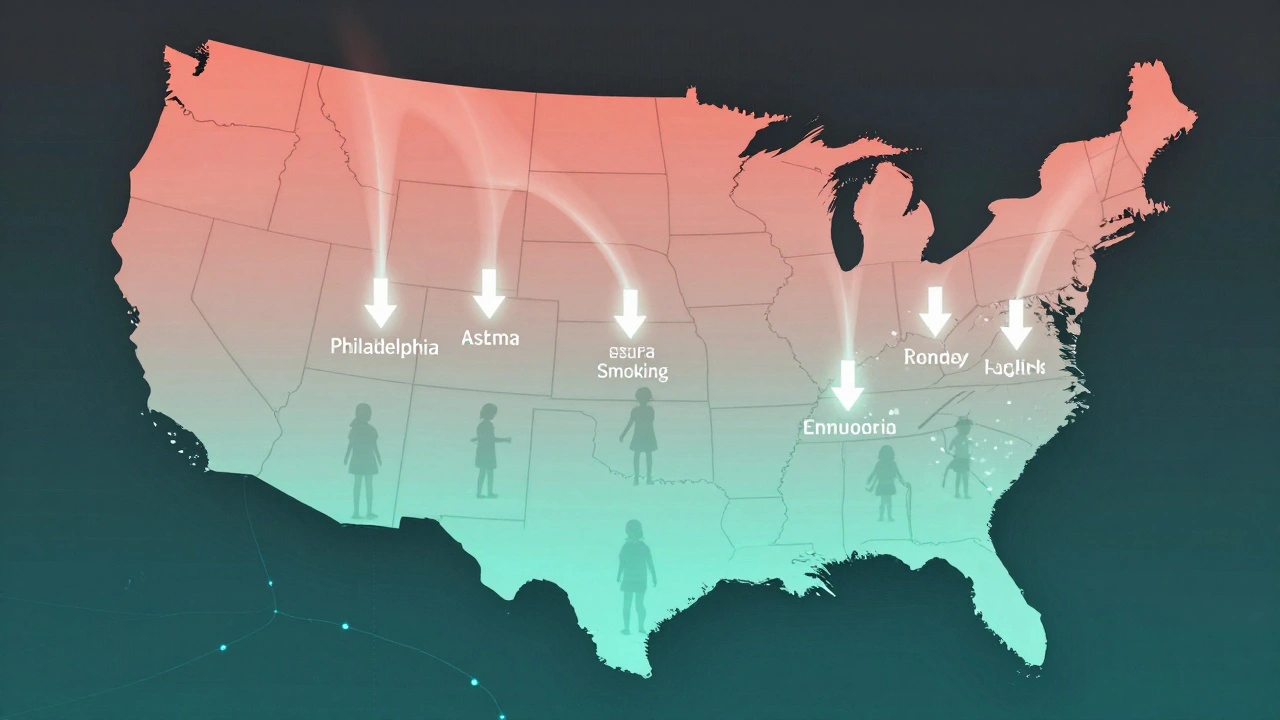

Unlike incidence, which tracks new cases, prevalence captures the full burden on the system. A policy that reduces hospitalizations for asthma might not stop new cases, but if it helps people manage their condition better, prevalence drops. That’s what happened in Philadelphia after they launched a citywide air filtration program in low-income housing in 2022. Asthma prevalence among children fell by 17% in two years - not because fewer kids got sick, but because fewer got seriously ill enough to need emergency care.

How Before-and-After Analyses Work

These studies compare data from the same group of people or places before a policy was enacted and after it had time to take effect. The key is controlling for outside factors. You can’t just say, "The ban worked because smoking went down," if the economy crashed at the same time. Researchers use statistical models to isolate the policy’s impact.

For example, when New York City raised the legal age to buy tobacco from 18 to 21 in 2014, they didn’t just look at citywide numbers. They compared smoking rates in NYC to similar cities like Boston and Chicago that didn’t change their laws. The gap widened over time - NYC saw a 13% steeper decline in teen smoking than the comparison cities. That’s how you know the policy did something.

Real-World Examples: Policies That Moved the Needle

- Water fluoridation in Michigan (2020): After Flint’s water crisis, the state expanded fluoridation to 12 underserved communities. Dental cavities in children under 12 dropped by 31% in three years.

- Universal mental health screenings in schools (California, 2021): Schools began routine depression and anxiety screenings. By 2024, diagnosed cases of untreated depression in teens fell by 28%, meaning more kids got help before their condition worsened.

- Expanded Medicaid in Kentucky (2019): After coverage expanded, prevalence of uncontrolled hypertension among low-income adults dropped by 19%. More people had access to regular medication and checkups.

These aren’t flukes. They’re repeatable outcomes. Each one used longitudinal data - tracking the same people or places over time - to prove cause and effect.

Why Some Policies Don’t Show Results

Not every policy change leads to a measurable drop in prevalence. Sometimes the reason is simple: the policy wasn’t enforced. In 2022, a Minnesota county passed a sugar-sweetened beverage tax. Sales of soda dropped 18% - but only in grocery stores. Convenience stores and gas stations kept selling them at full price. The tax didn’t reach the people who bought the most soda. Prevalence of obesity didn’t budge.

Another issue? Timing. If a policy takes years to change behavior, you need long-term data. A ban on vaping in public parks won’t reduce lung disease overnight. It takes time for people to switch habits, and even longer for health outcomes to improve. Researchers wait at least 24 months before declaring a policy a success.

The Hidden Data Gaps

Not all populations are tracked equally. Rural areas often lack regular health surveys. Immigrant communities may avoid reporting health issues due to fear or language barriers. This creates blind spots. A policy that looks successful in urban centers might be failing in towns 50 miles away.

For example, when Illinois expanded free HIV testing in 2021, urban prevalence dropped. But in rural counties, testing rates didn’t increase. Prevalence stayed flat - not because the virus spread, but because cases went undetected. Without better data collection in those areas, policymakers had no idea the policy wasn’t working everywhere.

What You Can Learn From This

If you’re a policymaker, public health worker, or even a concerned citizen, here’s what matters:

- Don’t assume a policy works just because it sounds good. Look for data before and after.

- Compare similar areas with and without the policy. Isolation matters.

- Wait at least two years before judging outcomes - health changes slowly.

- Check if the policy reaches everyone. If only some groups are affected, the overall prevalence won’t move.

- Push for better data collection in underserved areas. No data means no accountability.

The most powerful tool in public health isn’t a new drug or a fancy app. It’s consistent, honest data. When you track prevalence over time, you don’t need guesswork. You have evidence. And evidence changes lives.

What’s the difference between prevalence and incidence?

Prevalence measures how many people have a condition at a given time. Incidence measures how many new cases occur over a period. For example, if 100 people have diabetes right now, that’s prevalence. If 20 new people are diagnosed this year, that’s incidence. A policy might reduce incidence (fewer new cases) but not prevalence (if people already have it and live longer with it).

How long should you wait to see changes in prevalence after a policy change?

At least 18 to 24 months. Behavioral changes - like quitting smoking or eating less sugar - take time to stick. Health outcomes, like lower blood pressure or fewer hospital visits, take even longer to show up in data. Studies that look at less than a year often miss real effects.

Can a policy increase prevalence?

Yes - sometimes. If a policy improves early detection, like expanding free cancer screenings, more cases get found. That raises prevalence even if the disease isn’t spreading. It’s not a failure - it’s a sign the system is catching problems earlier. The real goal is reducing deaths and suffering, not just lowering numbers.

Why do some policies fail even with good data?

Because data doesn’t equal implementation. A policy might be well-designed, but if it’s underfunded, poorly communicated, or not enforced, it won’t work. For example, a city might pass a law requiring healthy school lunches, but if the cafeteria budget stays the same, they’ll just serve the same processed food under a new name.

Are before-and-after studies reliable?

They’re among the most reliable tools we have for policy evaluation - if done right. The key is using control groups, adjusting for trends, and using long-term data. When researchers compare a policy area to a similar area without the policy, they can rule out things like economic shifts or seasonal changes. That’s why these studies are trusted by the CDC and WHO.