Before 2013, if someone spent 12 hours a day playing video games, skipped meals, lost their job, or stopped talking to friends, most people shrugged it off as "just a phase" or "too much gaming." But behind the scenes, researchers were quietly collecting data that would change how we see addiction-not just to drugs or alcohol, but to digital experiences. Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) didn’t appear out of nowhere. It was built on years of clinical observations, brain scans, and global surveys. Here’s the real timeline of how it went from a fringe concern to a recognized condition.

1990s: The First Clues

In the early 1990s, psychologists in South Korea and China started noticing something unusual. Teenagers were disappearing for days-sometimes weeks-into online multiplayer games like StarCraft and Lineage. Clinics began reporting cases of extreme fatigue, weight loss, and even hospitalizations due to dehydration and sleep deprivation. These weren’t isolated incidents. In 2000, a study from Seoul National University tracked 300 adolescents who played over 10 hours daily. Nearly 40% showed signs of withdrawal when forced to stop: irritability, anxiety, and obsessive thoughts about returning to the game. This was the first solid evidence that gaming could trigger dependency patterns similar to substance abuse.

2013: DSM-5 and the Controversial Entry

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) released the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) in 2013. For the first time, it included a section called "Conditions for Further Study," and under it was "Internet Gaming Disorder." It wasn’t officially classified as a mental illness yet, but it was listed with nine criteria. To qualify, someone had to meet five or more of them over 12 months: preoccupation with gaming, withdrawal symptoms, loss of interest in other activities, lying about usage, using games to escape negative moods, and more. Critics called it premature. Supporters argued it was the first step toward validation. Either way, it triggered a flood of research. Universities in the U.S., Canada, and Australia began designing studies around it.

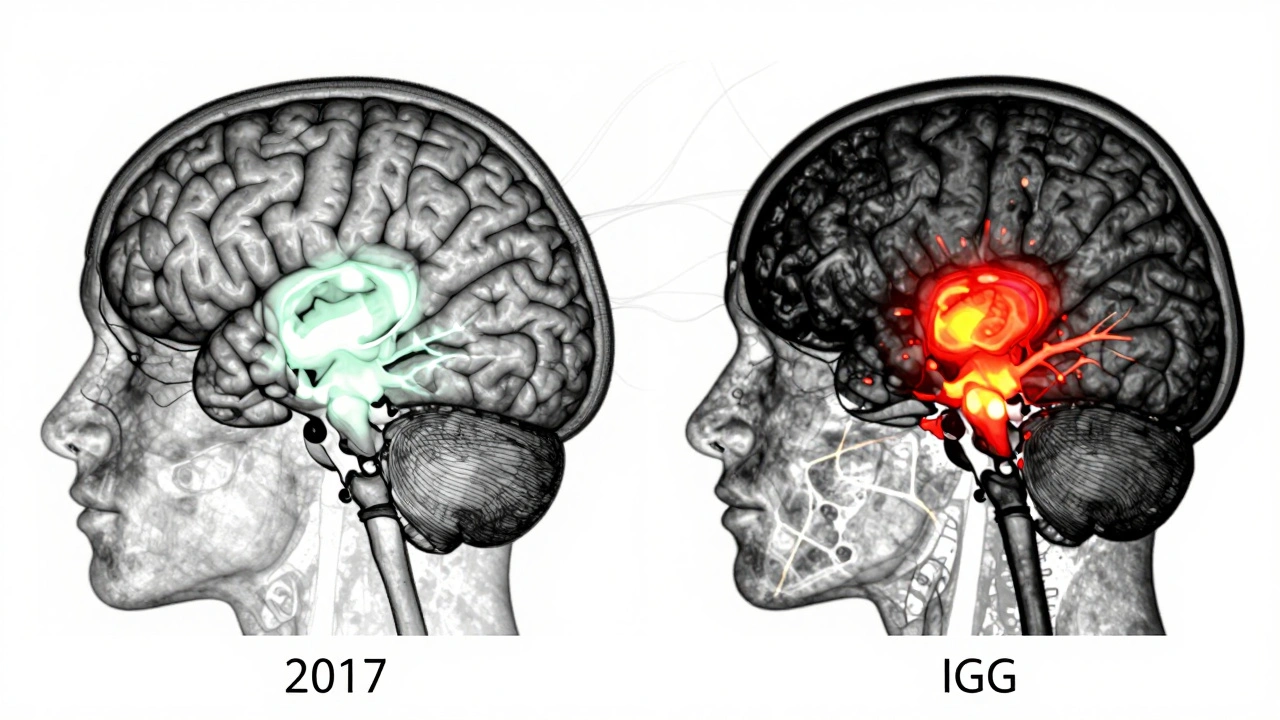

2015: Brain Imaging Confirms Physical Changes

In 2015, a landmark study from the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China used fMRI scans on 40 young adults diagnosed with IGD. They compared their brain activity to 40 healthy controls while they played a game similar to what they’d normally play. The results were startling. The IGD group showed reduced gray matter in the prefrontal cortex-the area responsible for impulse control and decision-making. Their reward systems lit up like those of people addicted to cocaine or heroin. This wasn’t just behavioral-it was neurological. The same year, a meta-analysis of 41 studies confirmed that IGD patients consistently had higher levels of cortisol (the stress hormone) and lower serotonin activity, mirroring patterns seen in pathological gambling.

2018: WHO Adds IGD to ICD-11

The World Health Organization took the biggest step in 2018 when it officially added "Gaming Disorder" to the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Unlike the DSM-5’s "for further study" label, this was a full diagnostic code: 6C51. The WHO defined it clearly: impaired control over gaming, increasing priority given to gaming over other activities, and continuation or escalation despite negative consequences. It had to last at least 12 months to be diagnosed. This wasn’t just a technical change-it meant insurance companies, health systems, and governments now had to recognize it as a real condition. Countries like Japan, South Korea, and Germany began funding treatment programs. Clinics opened in Beijing, Tokyo, and Berlin specifically for gaming addiction.

2020-2023: The Pandemic Surge

The global pandemic made IGD impossible to ignore. With schools closed, jobs remote, and social life online, gaming became the primary outlet for millions. A 2021 study from Harvard Medical School analyzed 12,000 adolescents across 14 countries. They found a 300% increase in cases meeting IGD criteria compared to pre-pandemic levels. The most alarming trend? Children under 12 were showing symptoms. One 9-year-old in Oregon was brought to a clinic after playing 16 hours a day for six weeks straight. His parents didn’t realize he was using a second device to bypass parental controls. This period forced researchers to rethink age thresholds and diagnostic tools. New screening tools were developed, like the IGD-20 scale, which uses shorter, more practical questions for use in schools and primary care.

2024: Treatment Protocols Begin to Standardize

By 2024, the field had matured. Three core treatment approaches emerged as most effective: cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) adapted for digital addiction, family systems therapy (since IGD often affects entire households), and digital detox programs with structured reintroduction. A randomized trial in the Netherlands showed that CBT reduced daily gaming time by 72% over six months, with 68% of participants maintaining improvement a year later. Meanwhile, tech companies began integrating voluntary usage limits into their platforms. Steam now shows weekly playtime summaries with warning alerts after 15 hours. PlayStation and Xbox added mandatory cooldown periods after 4 consecutive hours. These weren’t forced restrictions-they were nudges backed by behavioral science.

What’s Next?

The research isn’t over. Scientists are now exploring whether IGD is a symptom of deeper issues-like anxiety, ADHD, or social isolation-rather than a standalone disorder. Others are studying genetic markers that might predict vulnerability. One team at Stanford is testing whether neurofeedback training can help restore prefrontal cortex function. Meanwhile, governments are debating whether IGD should be covered under public health insurance. In Oregon, a bill passed in late 2023 to fund free counseling for teens with gaming disorder. It’s too early to say if IGD will be treated like alcoholism or depression, but one thing is clear: we can no longer dismiss excessive gaming as a choice. It’s a condition that rewires the brain, and it’s here to stay.