When someone spends 12 hours a day playing video games, skipping meals, losing sleep, and still can’t stop-even when it ruins their job, relationships, or health-they’re not just "into gaming." They might be dealing with something deeper: gaming disorder. And new brain scans are showing why.

What’s Really Happening in the Brain?

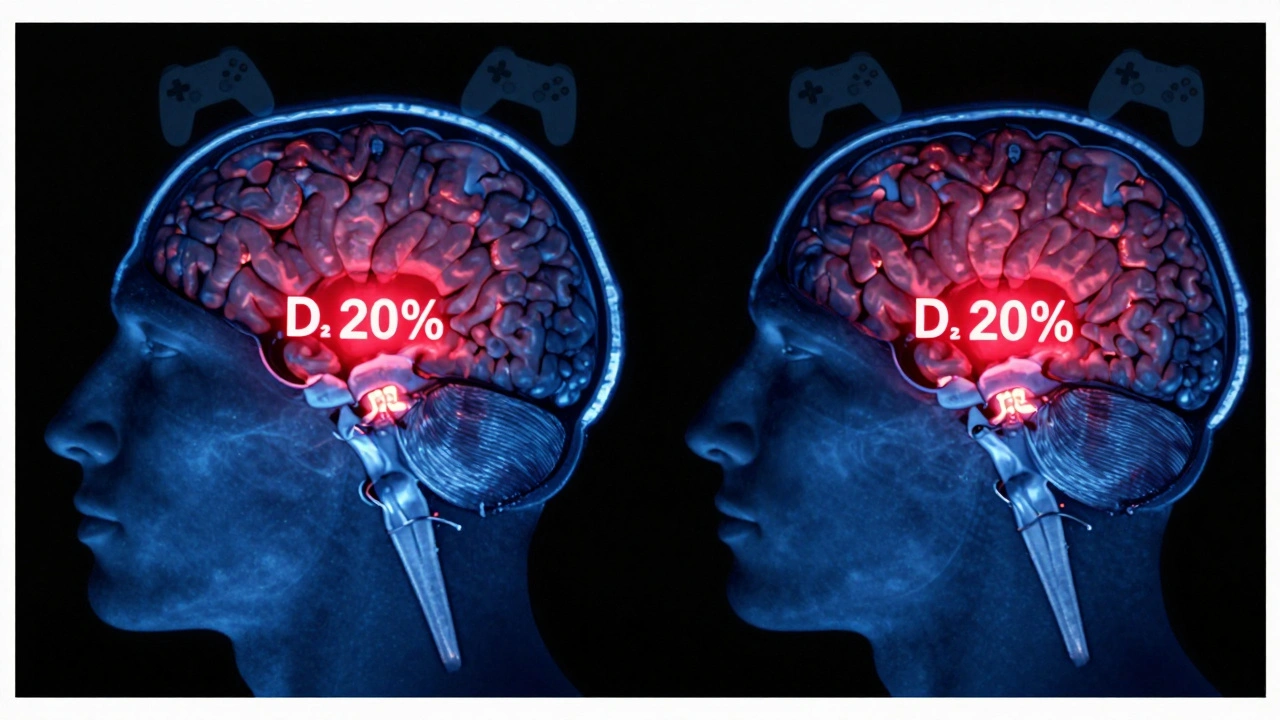

For years, people dismissed excessive gaming as a bad habit. But research from the University of Oregon and Kyoto University in 2024 found something startling: people diagnosed with gaming disorder have significantly lower levels of dopamine D2 receptors in their striatum-the part of the brain that drives motivation, reward, and habit formation.

This isn’t just a correlation. It’s a pattern seen in people with cocaine addiction, gambling disorder, and alcohol dependence. Lower D2 receptor availability means the brain’s reward system is dulled. It takes more and more stimulation to feel the same rush. So the person keeps playing-not because they love the game, but because their brain has become less sensitive to pleasure itself.

Why Dopamine D2 Receptors Matter

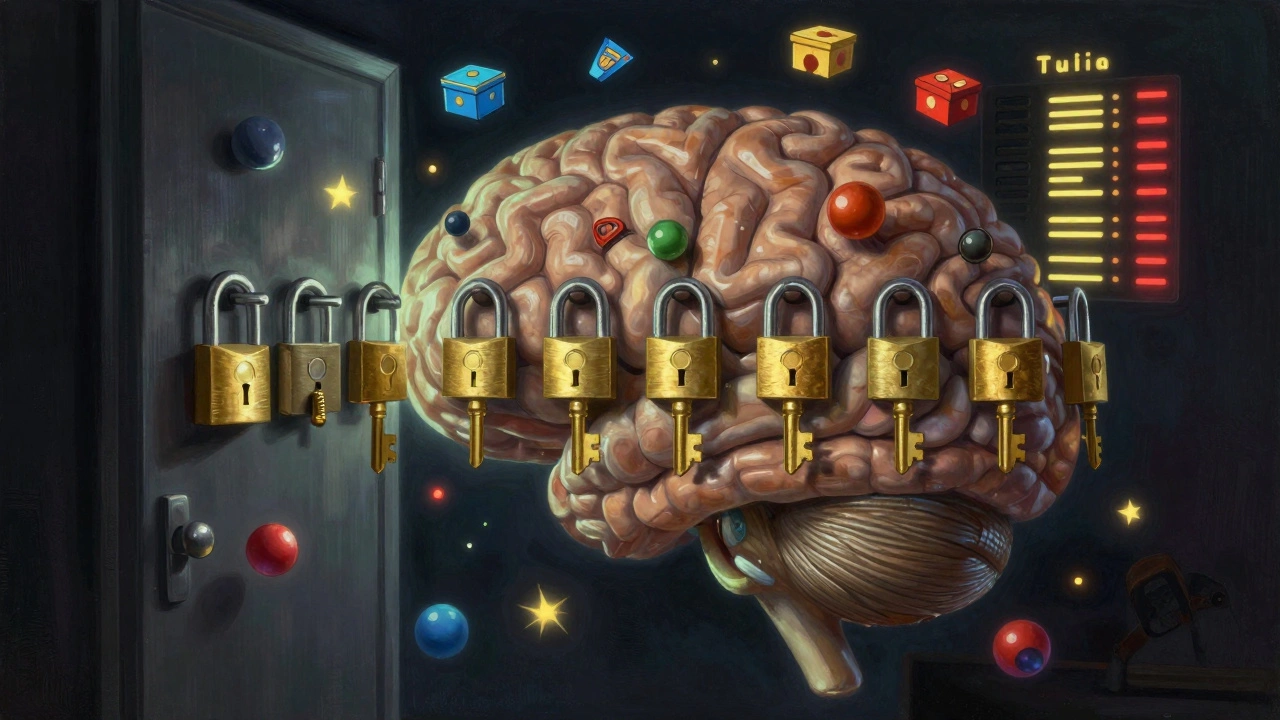

Dopamine is the brain’s reward chemical. When you score a kill in a game, finish a level, or unlock a rare item, dopamine fires. That’s why it feels good. But dopamine D2 receptors are the locks that let dopamine in. If there aren’t enough locks, the key (dopamine) can’t do its job.

Think of it like a door. If you have 100 locks on a door, even a weak key can open it. But if you only have 10 locks left, you need a much stronger key to get in. In gaming disorder, the brain has lost so many D2 receptors that normal game rewards barely register. The person needs longer sessions, harder challenges, or more intense stimuli just to feel anything at all.

Studies using PET scans show these receptor levels drop by 18-24% in people with gaming disorder compared to healthy controls. That’s similar to what’s seen in chronic cocaine users. It’s not about how much dopamine is released-it’s about how many receptors are left to receive it.

Is This Damage Permanent?

One of the most hopeful findings came from a 2025 follow-up study tracking 87 people with gaming disorder over 18 months. Those who reduced gaming to under 2 hours a day and replaced it with physical activity, social interaction, and sleep hygiene showed a 15% increase in D2 receptor availability. Not full recovery-but measurable improvement.

It suggests the brain isn’t broken. It’s adapting. Like muscles that weaken from lack of use, dopamine receptors can regain function when the brain isn’t flooded with artificial stimulation. But the window for recovery seems to narrow the longer the disorder goes untreated. People who had gaming disorder for over five years showed little to no recovery, even after quitting.

How Gaming Triggers This Change

Not all games are equal. Games designed with variable reward schedules-like loot boxes, random item drops, daily login bonuses, and leaderboard rankings-are engineered to exploit this system. They mimic slot machines. You never know when the next reward will come, so you keep pulling the lever.

Compare that to a game like Chess or a single-player story-driven title. These don’t trigger the same pattern. The problem isn’t gaming itself. It’s the specific design of hyper-stimulating, reward-driven games that hijack the brain’s natural reinforcement system.

One 2023 study found that players of mobile games with daily rewards and randomized loot mechanics had 31% more D2 receptor reduction than those who played strategy or puzzle games without these features. The design matters more than the time spent.

Who’s Most at Risk?

It’s not just teens. While gaming disorder is most commonly diagnosed in adolescents and young adults, the fastest-growing group is adults aged 25-35. Many are former gamers who returned during the pandemic and never stopped.

People with pre-existing anxiety, depression, or ADHD are at higher risk. Their brains already struggle with reward processing. Gaming offers a quick, controllable fix. But over time, it makes the underlying problem worse.

There’s also a genetic angle. A 2024 study of twins found that those with a specific variant of the DRD2 gene-responsible for dopamine D2 receptor production-were 2.7 times more likely to develop gaming disorder when exposed to high-reward games.

What Can Be Done?

There’s no pill to restore dopamine receptors. But there are proven strategies:

- Gradual reduction: Cutting back from 8 hours to 4, then 2, helps the brain recalibrate without shock.

- Physical exercise: Just 30 minutes of aerobic activity three times a week boosts natural dopamine production and D2 receptor density.

- Social reconnection: Real-world interactions-talking face-to-face, playing sports, volunteering-reactivate the brain’s natural reward pathways.

- Sleep hygiene: Poor sleep lowers dopamine sensitivity. Fixing sleep patterns alone improved D2 receptor markers in 42% of participants in one trial.

- Game design awareness: Avoiding games with loot boxes, streaks, and randomized rewards helps prevent relapse.

Therapy that combines cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with mindfulness training has shown the highest success rate-68% of participants maintained reduced play after one year.

Why This Changes the Conversation

This isn’t about willpower. It’s not about laziness or poor time management. It’s neurobiology. The brain physically changes. And that changes how we treat it.

When we call gaming disorder a "habit," we blame the person. When we see it as a brain adaptation, we treat it like addiction-with compassion, structure, and science.

More clinics are now using PET scans to diagnose gaming disorder, not just interviews. Insurance companies in the U.S. and EU have started covering neurobehavioral therapy for gaming disorder under addiction treatment codes. It’s no longer seen as a niche issue.

And for those who’ve spent years feeling guilty for playing too much? There’s hope. The brain can heal. But it needs the right environment-and time.

Is gaming disorder the same as addiction?

Yes, in brain terms. Gaming disorder meets the clinical definition of behavioral addiction. It involves loss of control, continued use despite harm, and changes in brain chemistry-especially reduced dopamine D2 receptor availability. The World Health Organization recognizes it as a diagnosable condition since 2018. It’s not just "addiction to games"-it’s addiction to the reward pattern those games create.

Can you recover without quitting gaming completely?

Some people can, but it’s rare. Most successful recoveries involve cutting back to under 2 hours per day, avoiding high-reward games, and replacing gaming with other rewarding activities. Complete abstinence isn’t always necessary, but uncontrolled play almost always leads to relapse. The goal isn’t to ban games-it’s to rebuild a balanced relationship with them.

Do all video games reduce dopamine receptors?

No. Games with predictable rewards, no loot boxes, and no streak systems-like puzzle games, strategy games, or single-player story games-don’t trigger the same brain changes. The problem isn’t gaming. It’s the design of games that use variable reinforcement schedules, similar to slot machines. These are mostly found in mobile games, online multiplayer titles, and free-to-play games with microtransactions.

How long does it take for dopamine receptors to recover?

In people who reduce gaming and adopt healthy habits, measurable improvements in D2 receptor availability show up in 3-6 months. Full recovery can take 12-24 months. But if gaming disorder has lasted over five years, recovery is much slower-and sometimes incomplete. Early intervention makes a huge difference.

Are there medications to help with gaming disorder?

No FDA-approved drugs exist specifically for gaming disorder. Some clinicians use medications like bupropion (used for depression and smoking cessation) to help regulate dopamine, but results are mixed. The most effective treatment remains behavioral: therapy, lifestyle changes, and environmental restructuring. Medication alone won’t fix the brain’s rewiring.

What Comes Next?

Researchers are now testing whether targeted neurofeedback training can help restore D2 receptor function. Early trials use real-time brain scans to teach people how to activate reward pathways naturally-without games. It’s experimental, but promising.

Meanwhile, game developers are starting to respond. A few companies have begun removing loot boxes from new titles and adding built-in play-time limits. One studio even partnered with neuroscientists to design a game that rewards players for taking breaks.

The science is clear: gaming disorder isn’t about being weak. It’s about biology. And biology can change. With the right support, the brain can find its way back to balance.