Every year, more kids spend hours in front of screens-not just playing games, but living inside them. Schools are seeing the shift: students zoning out in class, skipping meals, losing sleep, and snapping over small frustrations. It’s not just about being ‘on the phone too much.’ This is gaming addiction, and it’s showing up in hallways, locker rooms, and parent-teacher conferences. The good news? Schools can do something about it. And one of the most powerful tools isn’t a policy, a ban, or a lecture. It’s a well-planned assembly.

Why Assemblies Work When Other Methods Fail

Most schools try to fix gaming addiction with rules: no phones, no gaming during lunch, lockers checked for controllers. Those rarely stick. Why? Because they treat the symptom, not the cause. Gaming addiction isn’t about laziness or rebellion. It’s about escape, connection, and reward. A kid who feels invisible at home or lost in class might find a world where they’re powerful, heard, and in control.

An assembly changes the game. It’s not a lecture. It’s a shared experience. When students see a peer talk about losing a year of their life to Fortnite, or a teacher share how they watched their own child vanish into a headset, something clicks. It’s not fear that changes behavior. It’s recognition.

What a Successful Assembly Looks Like

Forget PowerPoint slides about dopamine. Skip the scary stats. Real change happens when students feel seen. Here’s what works:

- Start with a real story. Invite a former student-now 18, in college-who spent 80 hours a week gaming. Let them talk about how they lost friends, grades, and sleep. Not as a cautionary tale. As a person.

- Include a game designer. Yes, a real one. Someone who worked on popular titles. Ask them: "What do you know about how your game keeps players hooked?" They’ll admit to reward loops, timed rewards, social pressure. Students don’t trust adults. But they respect people who built the games they love.

- Use live demos. Show a 90-second clip of a player’s screen: their stats, their streaks, their daily login bonuses. Then show the same person’s calendar from that week. No sleep. No homework. No family dinner. The contrast is shocking-and real.

- End with choice, not control. Don’t say "Don’t play." Say: "What would your life look like if you took one day a week off?" Give every student a card: "I choose to try a digital detox for 24 hours. Signed: _______"

Who Should Be Involved

This isn’t just the counselor’s job. It’s a team effort.

- Students. Let them help plan it. Pick the speaker. Choose the video. Write the questions. If they feel ownership, they’ll listen.

- Teachers. One teacher should share how gaming affected their classroom. Not as a complaint. As a clue: "I used to think they were lazy. Now I see they’re exhausted."

- Parents. Invite them. Not to lecture. To listen. Many parents don’t know how deep this goes. A simple handout with three questions they can ask their child-"What do you love about the game?" "What do you miss when you play too much?" "Would you be okay with a one-day break?"-can start conversations at home.

- Local therapists. If your district has a mental health partner, bring them in. Not to diagnose. To say: "This isn’t rare. We’ve seen 12 teens this year with symptoms matching gaming disorder. It’s real. And it’s treatable."

Timing and Frequency Matter

Don’t wait until things get bad. The best time to run this assembly is early in the school year-September or October. That’s when habits form. By February, it’s too late for prevention. It’s damage control.

Run it once a year. Not every month. Not every quarter. Once. Make it count. If you do it too often, it loses its power. Think of it like a fire drill. You don’t do it every day. But when you do, everyone knows what to do.

What to Avoid

There are traps every school falls into. Don’t make these mistakes.

- Don’t blame parents. Saying "Your kids are addicted because you don’t set limits" shuts down the room. Most parents are trying. Some are overwhelmed. Some are working two jobs. Shame doesn’t help.

- Don’t call it "addiction" in the flyer. Use "screen habits" or "digital balance." The word "addiction" scares people. It makes them defensive. Save it for the talk, where context matters.

- Don’t promise a fix. You’re not solving this in 45 minutes. You’re starting a conversation. That’s enough.

- Don’t make it mandatory for everyone. Let students opt out. Forcing attendance breeds resentment. Let them choose to show up. Those who do will be the ones who need it most.

What Happens After the Assembly

The assembly is just the first step. Without follow-up, it’s a flash in the pan.

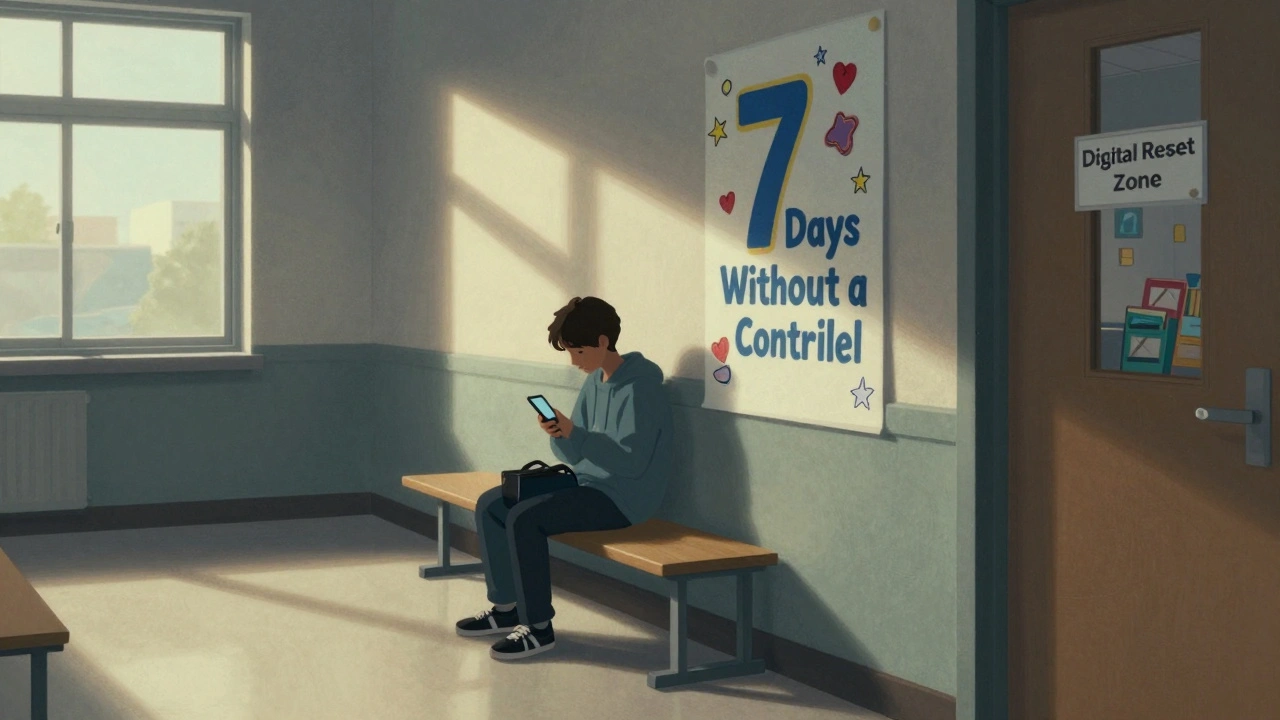

- Create a quiet space. Designate one room as a "digital reset zone"-no screens, comfy chairs, books, puzzles. Let students go there between classes if they feel overwhelmed.

- Launch a student-led challenge. "7 Days Without a Controller". Track participation. Not with punishment. With stickers. With a wall of names. With a pizza party for the class with the most completions.

- Train staff. Give teachers a one-pager: "Signs a student might be struggling with gaming." Include: sudden drop in grades, avoiding eye contact, irritability after screen time, lying about play hours.

- Share resources. Link families to free tools: the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Family Media Plan, or the nonprofit Screen Time a nonprofit that provides free, research-backed tools for families managing digital habits.

Real Results, Not Just Good Intentions

In a Portland middle school last year, they ran one assembly. No punishments. No bans. Just stories and a simple challenge. Three months later, 42% of students reported playing less than 3 hours a day. Before? Only 18%. The number of students referred for counseling dropped by 60%. Not because they were forced. Because they felt understood.

This isn’t about controlling kids. It’s about helping them reclaim their time, their attention, their relationships. A school assembly isn’t a magic fix. But when done right, it’s the first real conversation many kids have ever had about what’s really going on behind their screens.